When school isn’t accessible, what can we do to educate our youth? The obstacles faced by students with inadequate education are severe, and the challenges to getting that education are often overwhelming: violence, poverty, geopolitical conflicts, disaster, linguistic barriers, cultural hesitancy and disease can all create systemic barriers to school. These obstacles act on long time scales and can have impacts at any point during a student’s educational career, even before birth. For vulnerable children, school may feel like a fragile ideal, one that is hard to hold on to. Educators can, and should, look for how to meet students where they are: within their communities, and as part of them.

Research into helping students who have fallen out of traditional school environments points to a number of factors that are most effective in supporting education and integrating them into formal schooling:

- Acceptance and positive regard for students regardless of their circumstances

- Psychosocial support and counseling

- Cooperation with professionals in schools

- Use of local social networks and communities

- Personal relationships and peer support

But each community is as different as the challenges they face. Innovations that bring learning to nontraditional spaces often do so out of necessity - a response to the needs of the local community. Four innovations from the 2024 Global Collection; Nos Vemos en la Escuela, Home as a Learning Space, Juega Conmigo, and Last Mile Learning; offer instructive examples on how to support children where they are and to bring school to them.

Developing Personal Relationships

aesic, a Venezuelan organization dedicated to improving education for vulnerable groups, developed Nos Vemos en la Escuela with these principles in mind. Recognizing the needs of 3.5 million students who are currently excluded from the formal education system, in particular due to conflict, disasters and the COVID crisis, Nos Vemos en la Escuela (See you at school, in English) sought out to bring school to more spaces. It is carried out in institutions, schools, parishes, homes, dining rooms, cultural or community centers and hospital classrooms, among other places that serve as spaces - more than 80 spaces at the heart of their communities, which aesic calls Alternative Learning Centers.

A community space used as an alternative learning centre

By locating these centres where students are, Nos Vemos en la Escuela has been able to provide services ranging from hygiene and nutrition to psychological and anti-violence training, while simultaneously helping more than 12,000 children make up for lost learning in math and language skills. More impressively, they are able to do this both in Spanish and the variety of indigenous languages spoken in the communities they serve.

A key part of this success are the facilitators - some 518 local experts have been trained to provide the supports that their students need to get back to school. By embracing localised engagement, personal support, and fostering a culture of acceptance, Nos Vemos en la Escuela not only re-enrolled over 80% of marginalised children into formal education but also provided tailored services across diverse linguistic and community contexts.

Carolina Orsini, executive director of aseinc, shares with us in Spanish the changes she has seen after alternative learning spaces have been established: "An awareness of the importance of education, illiterate adults becoming literate alongside the children, communities in solidarity with the alternative centre and organising to furnish it. Some schools even find means to provide them with snacks, sports, and cultural activities." She emphasises that the ultimate goal is to help these communities bring their youth back into traditional schools - the program managers coordinate with the local school communities to facilitate the enrolment process.

Finding your community

Forefronting of local communities is the heart of this work - and has likewise been key to the successes seen by Juega Conmigo, an initiative throughout Guatemala spearheaded by ChildFund. The innovation (Play with me, in English), began as an initiative to teach Guatemalan parents to engage in play with their children as a crucial component to educational success. This early childhood play has important effects on math, creativity, social and academic skills, but is considered unnecessary and frivolous within many communities, particularly in rural areas. Child Fund's Chief of Party, Linda García Arenas, says their innovation works on multiple levels: "Play is a treasure! Since we started this path we discovered that not only is it fun but it allows us to share with other people and learn. We even discovered that playful activities between mother and child helps to cope with maternal depression. For this reason, the purpose of teaching families to play with their children collaborates with proposing experiences that expand children's neural connections and at the same time strengthens socio-emotional ties in the family: for us, it is a perfect match."

The COVID crisis required Child Fund to find innovative ways to reach their target communities: the traditional group sessions and home visits were no longer possible. "We had to develop a remote system to continue promoting early childhood development, specifically to promote playful parenting. We have communities without electricity, without access to the internet. So that’s why we chose radio to do our innovation,” Linda shares.

Juega Conmigo advocates for playful parenting

Juega Conmigo has undertaken enormous efforts to ensure their work can reach the homes that need it most. They converted their programming into engaging radio shows that were broadcast on the most popular stations in each area, and translated into the local Mayan languages that rarely have access to pedagogical content. Activities were developed to take advantage of materials that could be reliably found no matter the location - bottle caps, twigs, and scraps of fabric. Loudspeakers were mounted to motorcycles to visit isolated villages in the Guatemalan highlands disconnected from the electrical grid. The team at ChildFund relied on the expertise of their local partners, but, due to the urgency of the COVID pandemic, moved to implement the innovation before they could develop appropriate tracking measures.

Not only were families listening to it, they were gathering together and listening in their native languages. When we went to communities, we could see the toys that we had taught them how to make.

“At first we were blind, because we didn’t know how to measure radio. We didn’t know if families were actually going to listen to the radio. Some months later, we discovered that not only were families listening to it, they were gathering together and listening in their native languages. When we went to communities, we could see the toys that we had taught them how to make, just by listening to the radio. Of course, now we have a monitoring system and an evaluation system, but seeing the families doing the activities we were suggesting was amazing. That’s how we discovered that what we were doing was useful.”

There was one more unexpected benefit: male caregivers, now part of the education process, were becoming more involved in parenting - greatly expanding the understanding of what it means to be a parent.

Working alongside schools

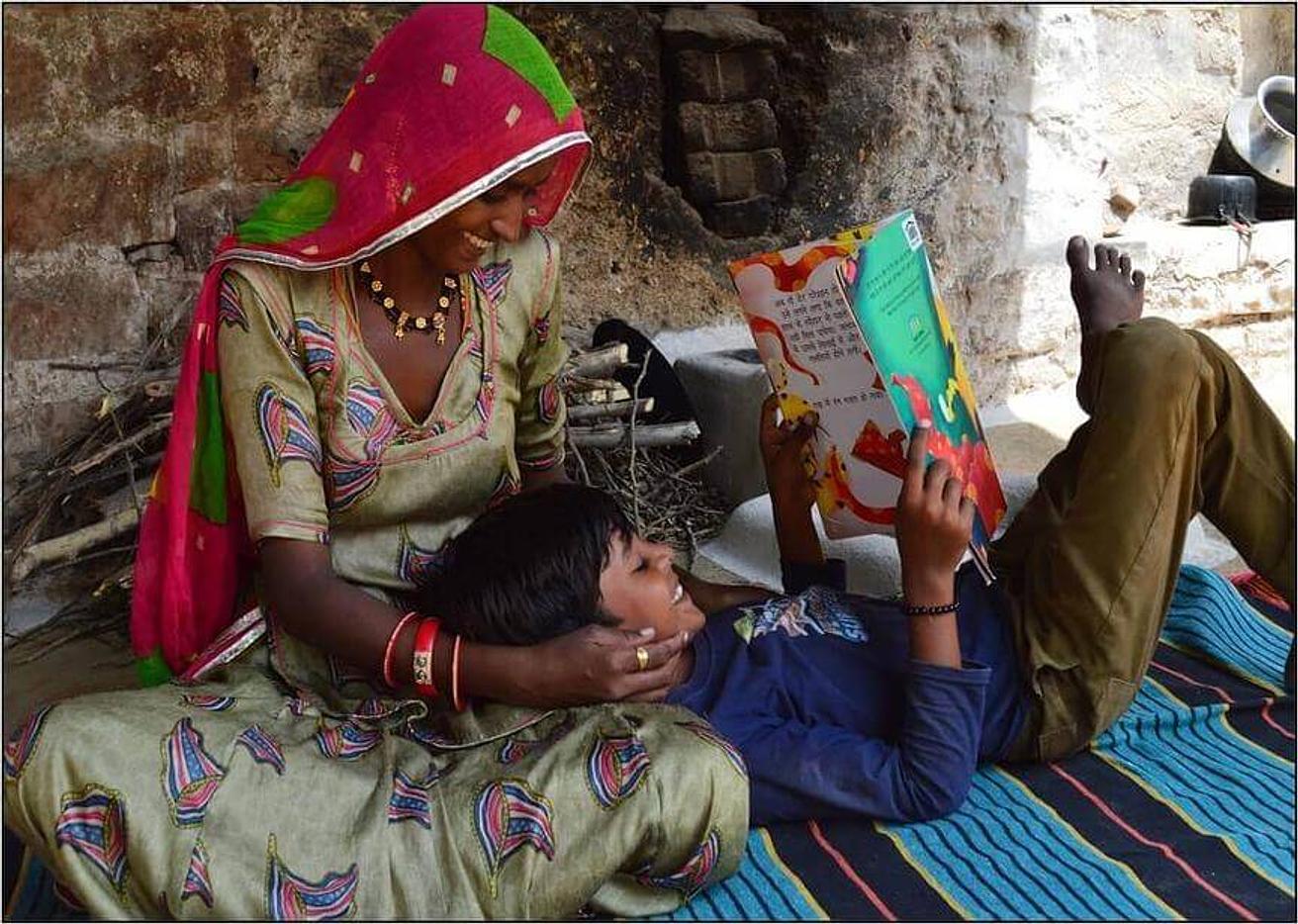

Involving parents into education is important not just for play, but also for reading. Students from impoverished backgrounds often enter school with language skills that are significantly below age level standards. The most effective remedy to this situation is reading at home - in targeted studies, parents reading to their children resulted in even higher gains than a similar course in school. Room to Read, based in India, have targeted the importance of literacy and reading but, just like Juega Conmigo, needed to adapt to the demands of the pandemic. As families adapted to school closures, Room to Read developed a programme to encourage schoolwork to continue during the pandemic.

The result, Home as Learning Space, has been implemented in Rajasthan and Jharkhand, two Indian states that differ widely along geographic, linguistic, socioeconomic and cultural lines. In order to meet community needs, Home as Learning Space’s fundamental ideas - a parent calendar to help maintain the habit of school, and structured, age appropriate and curriculum aligned activities - were adapted to the local contexts. The Rajasthani implementation focused on volunteer community engagement, where respected local leaders led community sessions to help parents dive deeper into the learning activities. In Jharkhand, teachers were recruited from schools to help parents in their homes. Home as Learning Space's adaptable approach, tailored to Rajasthan and Jharkhand's diverse landscapes, signifies a shift towards recognising that learning extends beyond the classroom, reaching and supporting over 30,000 children during the COVID pandemic.

Accepting the obstacles

The innovations discussed so far consider students that are in their home territory. Migrant student populations pose a greater challenge and perhaps none is greater than those of refugee populations. Last Mile Learning, an initiative from Street Child, is building spaces for learning where none have existed before. “The remote-based education support has been designed for the Rohingya refugee children who are living on the remote island of Bhasan Char in Bangladesh where traditional school, classroom and teaching supports are inadequate. The Rohingya refugees lack access to phones, sim cards, internet or even electricity. They don't have skilled teachers to run the classes, they don't have traditional school space, and not much NGO or donor support is available there to provide education support. Street Child's remote-based innovation model helps Rohingya refugee children in the island to have the education without any traditional school set up or teaching support,” shares Bangladesh Programme Manager Imitiaz Ridoy.

They don't have skilled teachers to run the classes, they don't have traditional school space.

These children face further challenges: what government curriculum that does exist is provided in Bengali or Burmese, while the students speak Rohingya. Rohingya is a language with no written component, making the development and distribution of lessons and learning materials more difficult. Last Mile Learning turned to an innovative, low cost approach: lessons recorded on solar powered MP3 players in language comprehensible to the students, targeted to their cultural context combined with reusable physical learning materials designed for self-directed use. The lessons are based on the Teaching at the Right Level framework, another HundrED innovation that has found widespread adoption for its ability to adapt to student’s needs across diverse contexts. The programme is designed to equip students with the basic literacy and numeracy skills they will need beyond the camps.

A self-directed group of learners

In lieu of traditional teachers, teenagers from the community have been recruited and trained to help. Imitiaz explains how, by involving community members, Street Child are looking to the future: “The adolescents are trained on last-mile learning pedagogies so even after the funding ends, they can continue the support the community with the children on a voluntary basis. If they get the chance to go back to Myanmar, their learning progression won't be affected. The adolescents’ engagement in the learning also ensures the sustainability of the innovative approach as it involves them growing up as sources of support for the community instead of hiring traditional teachers from outside.”

Last Mile Learning’s approach, integrating local language, accessible low-cost technology, and empowered community adolescents, serves as a beacon of effective outreach, bridging educational gaps for Rohingya refugee children, showcasing sustainable and innovative education beyond traditional methods.

In the realm of education, innovations like Nos Vemos en la Escuela, Juega Conmigo, Home as Learning Space, and Last Mile Learning signify the impact of effective outreach approaches. Through tailored support and community involvement, these initiatives have addressed educational barriers for marginalized groups. They've redefined learning by extending beyond traditional confines, adapting to local contexts, and fostering inclusive, community-based education. These innovations highlight that education thrives on acceptance, personalised aid, and collaborative community engagement. Their impact showcases the effectiveness of innovative outreach programs in reshaping educational experiences for those most underserved.

Want to learn more about impactful education innovations? Check out the 2024 Global Collection report.

Working on your own innovation? Submit your innovation to be considered for the next collection.