Fuji Kindergarten was showcased by the OECD as one of the best school buildings in the world and we’ve selected them to be one of our 100 examples of inspiring innovations in education. What’s all the fuss about? We spoke to architect Takaharu Tezuka, who designed the building, to find out more about it.

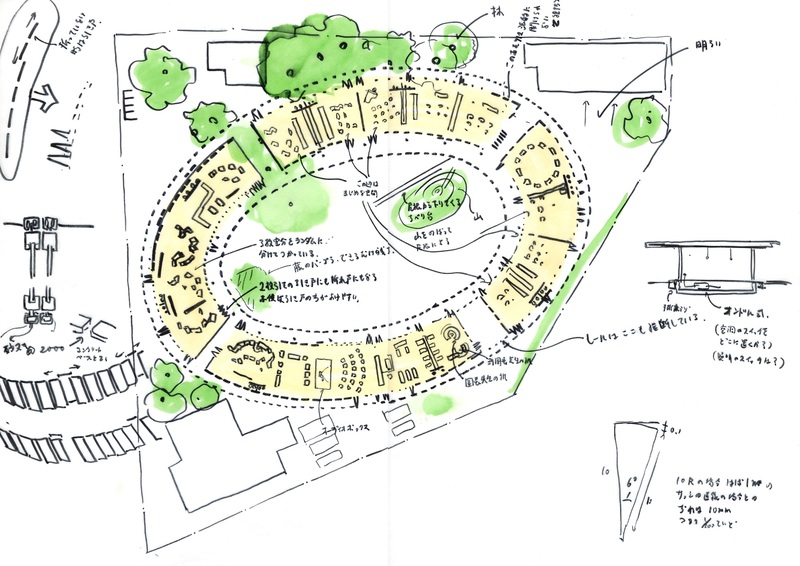

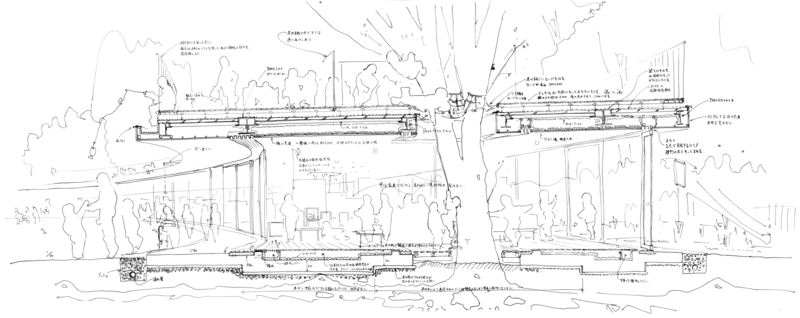

Fuji kindergarten was designed to have a circular roof, creating a never-ending playground for the children. Trees grow right through the middle of the classrooms, breaking the boundaries between outside and inside, and there are no walls between the classrooms – children are free to wander from one ‘room’ to another. The building also has sliding doors which are kept open up to two-thirds of the year to keep the flow from inside to outside open.

Essentially, the key aspect of this building was to break down barriers both physically and metaphorically.

The innovative architecture has also been recognised by TED, to get a sense of the playground in action check out Tezuka’s TED talk about the inspirations and realities of his design:

Having no walls means that the noise of one class mingles with another, creating a background noise or 'voice'. The purpose of this is to help keep young children calm. Tezuka explains the philosophy behind this idea as being similar to small children's sleeping preferences. When small children are put in a quiet room they often find it hard to fall asleep, they cry, and can therefore feel anxious. In crowded restaurants children often find it much easier to go to sleep.

The noise is therefore used to keep the atmosphere stress-free and restful, which appears to be working. Although the school has thirty children in attendance who have been diagnosed with autism, none of the children display signs of autism whilst at the kindergarten. The relaxed free nature of the environment clearly helps them to be a part of everyday school life without any stresses or worries.

The circular roof and openness of the whole building inspires movement. Children have been simply ‘left alone’ and so all movement and all learning is spontaneous. As a result children move more than in other kindergartens, five times more than the average child in kindergarten according to their research.

The design of the building helps them to be self-discovering. They decide how and where they want to play, what class they want to listen to... effectively how they want to learn! The educational methods in the school employ the Montessori method where self-led learning and learning through play are at the centre of how to educate. The building does everything it can to help this to happen.

The Montessori method still seems like a futuristic idea of education, even though it was actually conceived of a century ago. The design of the building helps to facilitate the educational methods that Montessori promotes, but it is not essential, it is the philosophy and the mindset that are most important. As Valerie Hannon, Director of Innovation Unit, explains, ‘a personalized learning environment will be one where young people feel valued, feel known, feel that their interests are important and where learning is anywhere and everywhere.’

This can be employed anywhere, no matter in what building and with what budgets. What the Fuji Kindergarten manages to do is to create an environment which enhances these core educational values.

Metin Ferhatoglu, Director of Technology at Robert College in Istanbul, told us what he thought made a better learning environment, ‘when I’m relaxed I learn better. A better environment feels like home.’ This is arguably the exact effect that Fuji Kindergarten has on the pupils and is one of the keys to its success.

Self-led learning gives children independence and allows them to relax which is what the Fuji Kindergarten is designed to do. Tezuka argues that when children learn something independently they are more likely to retain the information, but when they are forced to learn something it is more likely they will forget the lesson later. Surely it makes sense to allow children to follow their own learning path, rather than to force one on them?

Another of the key aspects for the building’s design was inclusion.

As the world becomes increasingly globalized with people of different cultures able to travel more easily, work internationally, or move to a new country, it is vital for schools to help create a future where its citizens are comfortable and accommodating for people different from themselves, and can be accepting and excited by differences.

The key brief for the building was for it to allow the school to feel like a family, even though the children are all from different backgrounds. Tezuka clearly took this message to heart as it is obvious to see how this has influenced all design decisions to create the building.

Essentially, the key aspect of this building was to break down barriers both physically and metaphorically.

"

Promotion and monetary value from the design aren’t important, as became clear when we asked Tezuka about promoting his design he replied, ‘We don’t promote our innovation because we are not a donut shop! We want the kids to be happy.’ Tezuka continued, ‘It is the idea that there should be no boundaries in the world that is the most important thing. We want to have Islamic people, Christian people, Buddhist people in the same building. Japan is only one place - we can bring everyone into one circle so they can see how we all link.’

It is clear the concept of the kindergarten was never driven by acclaim or money. At the heart is the children and the desire to help to create a better, more inclusive society. The designer is thrilled to have the backing of the OECD simply because he now has a larger voice, which he can use to spread helpful and healthy ideas.

Having diversity in the kindergarten isn’t just a ‘nice thing to have’ but it’s integral to the school’s values and ecosystem. There are currently thirty autistic children and one physically disabled child who uses a wheel-chair at the school, along with children from all different backgrounds.

One of the most important things about the kindergarten is that it is inclusive of everyone. They believe that if you only create an environment for a small section of the student population then you are creating a small society and a hierarchy forms. The children at the kindergarten are treated wholly, no matter the different cultures, religions, races, or abilities. There are no boundaries of any sort.

Just as the building is a simple infinity with no end, as are the relationships between the students and the teachers. The building’s aesthetic mirrors the principles and ethics of the school entirely.

The kindergarten has garnered lots of interest internationally, but it’s not easy to just implement the same concept somewhere else. If someone does have the resources to, then the school requires for them to come and work at the school for at least a month so they can see how it all really works, and to learn about the importance behind the concepts. They want to make sure that it’s not only the beauty of the building that people are seeing, but the education too.

Of course most schools don’t have the budgets necessary to create such an architecturally inspiring building, however the common themes in many of these high-budget innovations remain the same as low-budget innovations at the core. Student-led learning, freedom for personalization, for young children to learn through play and for older children to learn through self-discovery or projects. These are all concepts that keep reoccurring and which you don’t need to innovate a whole building to achieve.

In terms of improving learning environments the key thing is to empower the children, to give them freedom to learn independently, and to inspire a love for learning.

Physical learning environments are important too, but they are secondary to this core. Better lighting, fresh air, and making sure that children are comfortable are all important aspects of a physical learning environment. If the natural world and outside time can be included, that’s great, but the core is making kids passionate – and for that you don’t need a huge budget.

Fuji Kindergarten shows how all these ideas can feed into one another to create an education utopia. Can we all go back to kindergarten now please?