When most of us talk about poverty and how to end it on a mass-scale, one of the first things that come to our minds is the role of modern education. Indeed, politicians, business leaders, development actors, stakeholders of civil society, and – of course – ‘educators’ themselves keep on preaching about the key importance of what they call access to quality education in the heroic ‘fight against poverty.’ Almost like a silver bullet, modern education seems to have become the new mantra to finally and ultimately end poverty, once and for all.

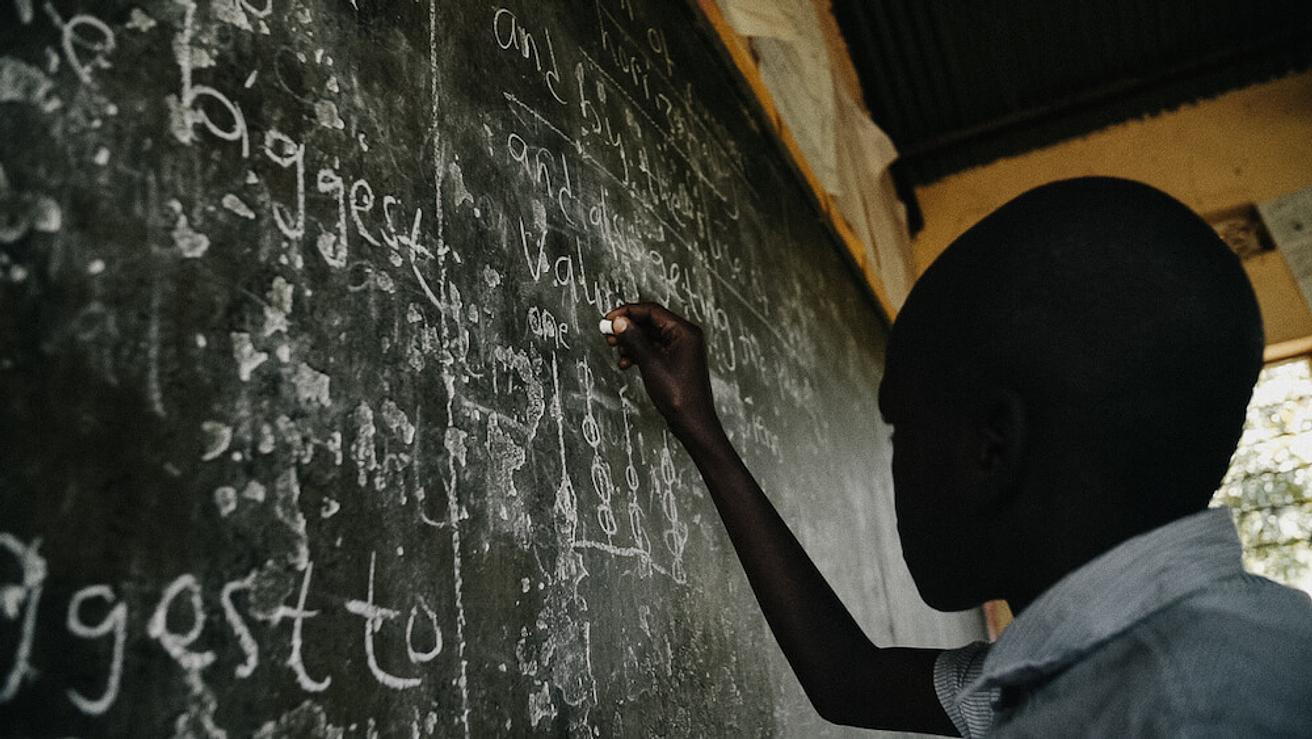

Let us explore this tragic and often unknown story of modern education now in more detail. First of all, what we refer to here as ‘modern education’ is what the above range of ‘experts’ from politicians to educators (and those who call themselves experts anyways) understand as mainstream schooling (both state-led and private-sector led), i.e. the age-specific, teacher-led processes requiring full-time attendance and a compulsory curriculum.

This model has its origins in the bygone era of industrialisation which required to ‘produce’ an efficient, subservient labour force carrying out repetitive, standardised tasks. This labour force in the making was better not to develop any creative skills, critical thoughts or (r)evolutionary ideas that might challenge the hegemony of the industrial elites and their capitalist model of exploitation which school education – till today – naturalises as the one and only way of ‘how things are’ and ‘how things ever can be.’ In other words, “capitalism requires increasing numbers of workers, citizens and consumers who willingly do what they are told to do and think what they are told to think. The production of such human capital is the most fundamental role schools play in a capitalist society” (Martell, 2005, p5; quoted in Hill and Kumar, 2009).

On the other side, a key idea for the capitalist-industrialist system of exploitation, the division of labour, wage work, the owning of the means of production by a small elite and the ever-growing consumption of goods by the general population – without which the capitalist system indeed does not work at all – is to make people dependent on salary-based work through which they need to buy necessary (and unnecessary) goods and items. In other words, schooling needed and needs to de-skill people and make them into wage-labourers and consumers rather than into creators and producers.

This is encapsulated in today’s prevailing Human Capital Approach to education, promoted heavily by the World Bank, all mainstream development organisations, intergovernmental organisations, and national governments. As such, “human capital education promises students higher incomes that can be used to purchase more and more products” (Spring, 2018, p305). In other words, modern education aims to transform independent, capable human beings into incapable, (market-)dependent consumers who keep the consumerist market economy going (see Spring, 2006). A meaningful life is reduced to and equated with being able to perpetually consume goods and products.

This becomes also clear when looking at the origins of compulsory mass schooling in the U.S. from where the modern education system spread across the globe.

Many famous ‘panics’ of nineteenth-century America was caused in part by the hangover from early federal times and colonial days when the common ideal was to produce your own food, your own clothing, your own shelter, your own education, your own medical care, your own entertainment, etc. The common population was still insufficiently conditioned to be interdependent and specialized (Gatto, 2012, p28).

Today, coupled with the increasing demands for global, compulsory schooling clothed in moralistic arguments, we can see how modern education “functions to discipline individuals in a manner that increases the productive power that their bodies offer to the economic system while simultaneously diminishing their power to resist economic exploitation and the political system that initiates that exploitation by compelling students to attend school in the first place” (Gabbard, 2012, p36). Similarly, according to Hill et al. (2017, p230), the contemporary education system conditions the child for a career of exploitation, inequality, and differentials, conformity, and passivity; it lowers expectations and confines and fragments a holistic outlook into myriad specialist skills that block the attainment of the bigger life picture.”

Furthermore, it is no coincidence thus that until today, schools exhibit a clear bias against manual labour and practical skills. At the centre of schooling, then, stands the belief that there is only one – the modern, individualist, consumerist, capitalist – way of life that is worthwhile and meaningful. Therefore, in today’s common-sense logic of modern education, farmers, peasants, manual labourers, ‘dropouts,’ indigenous people, forest dwellers, and anyone and everyone else pursuing ways of life that deviate from this path in the slightest are seen as ‘uneducated’ and in need of modern education to finally be able to live their lives in meaningful ways as consumer-citizens.

As recent Indian high school graduate Akshat Tyagi accordingly observes,

“those who do more manual jobs are thought to be unfit for children to be friends with, and their interaction with them is kept at lowest possible levels. I have seen schools where they make sure you do not talk or even face the janitors, housekeepers or drivers. They might take you on a class trip to the school gardener for learning about seeds, they will not let you come to the same gardener every day for learning something other than what the curriculum prescribes. Such a practice will be termed as a wastage of your time. This is probably what many have described as the ‘caste system of modern knowledge,’ in which these physical laborers are treated as untouchables and the presumed intellectuals are placed at the apex” (Tyagi, 2016, p21).

What becomes clear then is that until today, the modern education system is inherently tied to the capitalist mode of exploitation. Rather than conceiving of education as a tool to question, challenge, shape and re-shape society, mainstream education actors conceptualise ‘education’ as a reflection and extension of existing, contemporary society – what Émile Durkheim referred to as the socialisation function of education. As critical educationist Paulo Freire (2013, p76) further tells us, “this concept [of education] is well suited to the purposes of the oppressors, whose tranquillity rests on how well people fit the world the oppressors have created, and how little they question it.”

We can address the last doubts about this when looking at the relationship between a worldwide phenomenally increased access to

modern education and the global development of inequality and poverty which, other than what mainstream commentators tell us, show a negative correlation. Global inequality, poverty and living in precarious conditions are increasing despite the ever-growing access to education. As anthropologist and economist Jason Hickel’s research based on a realistic yet still moderate poverty line of USD 7.40 per day shows, “the number of people living under this line has increased dramatically since measurements began in 1981, reaching some 4.2 billion people today” (Hickel, 2019).

What we all finally need to start realise is that reforming the existing education system simply will not yield any change – it will not eradicate poverty but cement and perpetuate it. The modern education system, by default, is designed to keep the exploitative structure of capitalist society in place. This is why Project DEFY strives to implement alternatives to mainstream education rather than alternative, mainstream education. We challenge the system by giving power back into the learners’ hands and helping them to discover their own interests, acquire the skills they want to gain, and create their own projects relevant to their own lives. This is done through a low-cost, easily adaptable model of self-designed learning.

References

Freire, P. (2013). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Gabbard, D. (2012). Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools. In Haworth, R. H. (ed). Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective actions, theories, and critical reflections on education. Oakland, CA: PM Press, pp. 32-46.

Gatto, J.T. (2012). Weapons of Mass Instruction. Indore, India: Banyan Tree.

Hickel, J. (2019). Bill Gates Says Poverty is Decreasing. He couldn’t be more wrong [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/29/bill-gates-davos-global-poverty-infographic-neoliberal [Accessed 01 Oct 2019].

Hill, D., and Kumar, R. (2009). Global Neoliberalism and Education and Its Consequences. New York: Routledge.

Hill, D., Greaves, N.M., and A. Maisuria (2017). Embourgeoisment, Immiseration, Commodification – Marxism Revisited: A critique of education in capitalist systems. In Hill, D. (ed). Class, Race and Education under Neoliberal Capitalism. Delhi: Aakar Books, pp. 210-

237.

Spring, J. (2006). Pedagogies of Globalisation. Pedagogies, 1 (2), pp. 105-122.

Spring, J. (2018). American Education. (18 th ed). New York: Routledge.

Tyagi, A. (2016). Naked Emperor of Education: A product review of the education system. Chennai: Notion Press.

You can find out more information about Project DEFY on our website or innovation page.